-

Campuses

- Men's Colleges in the United States

- Wagner College (USA)

- Gustavus Adolphus College (USA)

- Springfield College (USA)

- University of Portland (USA)

- Saint John’s University [Collegeville, MN] (USA)

- Montana State University (USA)

- University of St. Thomas (USA)

- Reading University (UK)

- Kennesaw State University Men (USA)

- Books

- Contact

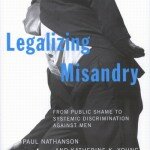

Legalizing Misandry

From Public Shame to Systemic Discrimination against Men

![]()

Paul Nathanson and Katherine K. Young

![]() Cloth (0773528628) 9780773528628

Cloth (0773528628) 9780773528628

CA $49.95 | US $44.95

Lurid and sensationalized events such as the public response to Lorena Bobbitt after she cut off her abusive husband’s penis, prurient fascination provoked by Anita Hill’s allegations about Clarence Thomas, and the exploitation of the mass murder of fourteen women in Montreal have been processed through popular culture since the 1990s to produce pervasive misandry – contempt for men, the counterpart of misogyny.Paul Nathanson and Katherine Young believe that this reveals a shift in the United States and Canada to a worldview based on ideological feminism, which presents all issues from the point of view of women and, in the process, explicitly or implicitly attacks men as a class. They argue that ideological feminism is silently reshaping law, public policy, education, and journalism.

Legalizing Misandry offers lively and compelling evidence to demonstrate the pervasiveness of this new thinking – from the courts, classrooms, government committees, and corporate bureaucracies to laws and policies affecting employment, marriage, divorce, custody, sexual harassment, violence, and human rights.

Legalizing Misandry offers lively and compelling evidence to demonstrate the pervasiveness of this new thinking – from the courts, classrooms, government committees, and corporate bureaucracies to laws and policies affecting employment, marriage, divorce, custody, sexual harassment, violence, and human rights.

__________________________________

Following on their study of the systematic hatred of men (misandry) in the popular media–SPREADING MISANDRY–two Canadian scholars present in this volume the second of a trilogy on the topic. The third will discuss misandry as it is being proselytized in college and university classrooms. They have no need for shocking journalistic revelations and rhetoric, but rely instead on sober, close examination of court decisions that have slowly but surely changed the way men are treated under the law in Canada and the United States. The authors show how interest groups, lobbying and media pressure have leveraged a sea change in the treatment of men, especially as husbands and fathers. Their position is ethical. The focus of their examination is ideological feminism’s effect on the framing of legal sanctions by our nation’s courts that are stacked against men. As a result of the influence of ideological feminism, certain topics may not be discussed in academe, the media will always support its agenda, and increasingly in the home, husbands and fathers are identified as dangerous and evil. Demonizing men in this way is the work of misandry. Its sources are complex, but they rest solidly in ideological feminism. The authors’ plea is for reasoned consideration of misandry and exposure of its motives. After reading this book, no one can fail to admit that we have reached a point where it is increasingly thought to be a shame to have been born male in North America. And we cannot forget that what is promoted here soon sends out spores to settle and grow elsewhere in the world. For now, this reader is grateful to the authors of this volume in the series of their studies for their courage in offering a point of view that those who are in academe know quite well MAY NOT be brought up in committee and faculty meetings and, soon, in all classrooms.My worry is above all for boys, the sons and students of men who are portrayed as evil, not only in the popular media but also increasingly in the eyes of the law. That boys are leaving school should not surprise us at all. That fathers are leaving their sons is also no less unpredictable in such a climate. Scholars of divorce may find a fuller understanding of their topic by reading this volume of Nathanson and Young’s trilogy.

It must be made clear that this is NOT an exercise in victim studies. Nor do the authors call for a counter-revolution to the positive feminism that brought women into the workplace and politics. They make no declarations. Instead they present evidence and examine arguments.

This is an important work in ethics, gender studies, and history. It deserves wide readership, media exposure, and discussion in academe. — Miles Groth, PhD